Coffee School

The Coffee school is the result of Cafés Baqué opting to promote the culture of coffee.

A meeting point for professionals from the catering industry that provides full training on the world of coffee and the main aspects for achieving a quality cup of coffee, including the following four key aspects: raw materials, grinding, machine and hand.

We train catering industry professionals so that they can get the most from the product, serving better quality coffee until they become true baristas.

In addition, we take the Coffee School to different catering industry training centres, where we train future catering industry professional.

COURSES

Barista course

Content:

- Coffee and the barista

- Milk emulsion

- Barista competition

- Demonstration

- Latte art

- Cappuccinos

- Practical exercises

Duration: 8 hrs (2 days)

Cost: €300

The world of coffee

Content:

- History

- Botany

- Blend roast and packaging

- Classification and quality

Duration: 3 hrs

Cost: €80

Professional tasting

Content:

- Brazilian tasting protocol

- Basic flavours and aromas

- Tasting conditions

- Tasting sheet

- Single-origin tasting

- Final evaluation of the tasting

Duration: 4 hrs

Cost: €200

Espresso

Content:

- Types of coffee

- Blend

- Grinder

- Machine

- Origins of latte coffee emulsion

Duration: 3 hrs

Cost: €80

Latte art and coffee combinations

Content:

- Milk emulsion

- Latte art

- Coffee combinations

- Practical exercises

Duration: 3 hrs

Cost: €100

HISTORY AND ORIGINS

Coffee is originally from Ethiopia, formerly Abyssinia, and more specifically from the Kaffa region, which is possibly where the name coffee comes from. The legend goes that around the 7th century, a shepherd called Kaldi noted a strange reaction in his flock of sheep after they had eaten the fruit and leaves of a plant that he didn’t recognise. The animals were unsettled, nervous and much more active.

Given the reaction, he decided to collect the fruit and leaves of the plant and prepare an infusion, the flavour of which he disliked so much that he threw the rest of the fruit into the fire. He was then very surprised to notice a very appealing aroma that made him prepare a new infusion, though this time with roasted beans. After drinking the infusion, Kaldi the shepherd experienced a euphoria that was as strange as it was unknown to him, which lead him to inform the Prior of the Chehodet Monastery.

There, after a number of tests with the seeds of these plants, the Prior discovered that once roasted and ground, a pleasant drink was obtained that helped him during long nights of vigil. This new drink became very popular and was introduced to all of the monasteries. Later on, the COFFEA plant (the tree that produces coffee) was taken to Arabia, where it became one of the most popular drinks among pilgrims on their way to Mecca. From the African continent, the COFFEA plant was exported to Central and South America.

THE COFFEE PLANT

The Coffea plant is a tropical bush from the COFFEA genus, which belongs to the RUBIACEAE family.

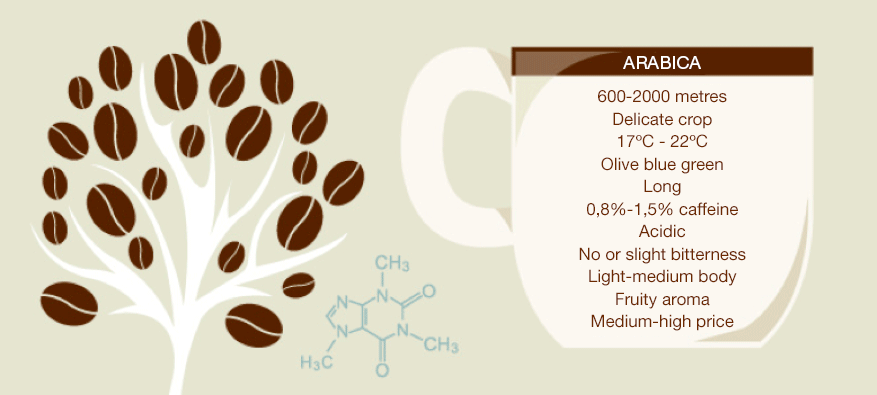

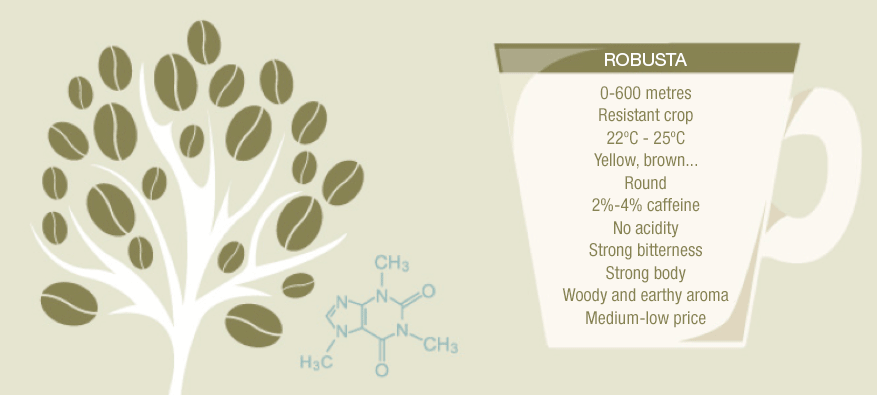

There are ten species: Arabica, Bengalensis, Canephora, Congensis, Excelsa, Gallienii, Bonnieri, Mogeneti, Liberica and Stenophylla. The most important of which are ARABICA, with all of its sub-species (CATUAI, CATURRA, TIPICA, BOURBON, TIMOR, CATIMOR, MOCKA, etc., currently more than 700 varieties), and CANEPHORA, whose main variety is ROBUSTA.

The global production of coffee is at around 140 million sacks approximately, which are 60-70 kg. Of this production, 65% is made up of ARABICA coffee beans, whereas the remaining 35% is made up of ROBUSTA coffee beans.

ARABICA coffee beans are floral and fruity, with hints of chocolate and citrus, whereas ROBUSTA coffee beans are woody and bitter.

The ARABICA plant is more delicate, whereas the ROBUSTA plant is much more resistant.

ARABICA plants are grown at an altitude of between 600 and 2,000 m (the higher they are, the more acidic the coffee bean), whereas the ROBUSTA coffee plants are grown from sea level to an altitude of 600 m.

Associated with altitude is temperature; the higher up the mountain we go, the lower the temperature, which means that Arabica plants are grown at temperatures below 22ºC..

The ARABICA coffee bean is long, whereas the ROBUSTA is round, determined by genetics.

In the ARABICA coffee bean, which is humid in nature, the groove can normally be seen clearly, whereas in the ROBUSTA, it can hardly be seen or is less obvious, as the latter does not usually undergo a washing process.

The colour of the ARABICA coffee bean is blue-green or olive green, whereas the ROBUSTA is yellow or brown, also due to its dry treatment.

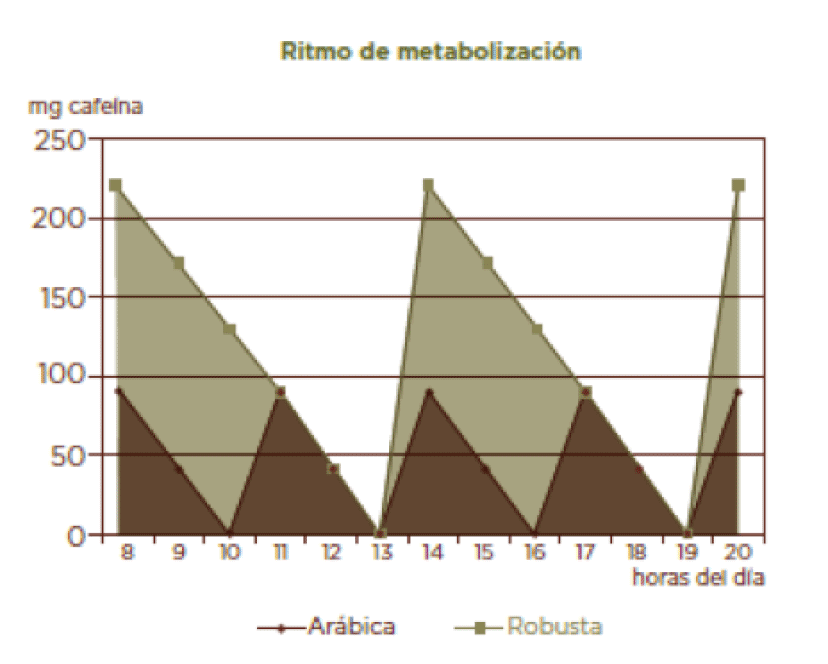

The concentration of caffeine in ARABICA coffee beans is 0.8-1.5%, whereas the concentration in ROBUSTA coffee beans is higher, 2-4%, almost twice the amount.

The caffeine content per espresso cup is 70-100 mg for ARABICA and 180-250 mg for ROBUSTA.

The COFFEA PLANT is one of the few plants that flowers and bears fruit at the same time. The tree, which has a conical shape, is characterised by the flexibility of its branches, deep green leaves and a white flower with a pleasant smell of jasmine.

The berry, cherry or drupe, as the FRUIT of the COFFEA plant is known, is collected when it has turned a deep red colour and consists of the following parts: PULP, MUCILAGE, PARCHMENT AND BEAN.

Not all Coffea plants are the same. Depending on their specific characteristics, they bear a different fruit. Arabica coffees (Central America, South America, Asia and East Africa) and Robusta coffees (mainly Africa and also Brazil and Asia) amount to 98% of the global production.

ARABICA COFFEE:

Arabica coffee comes from Ethiopia and has many varieties, differentiated by the fact that they grow in different soils, at different altitudes, in distinct climates or because they are subject to different factors. Some of these varieties are: typica, bourbon, java, criollo, etc.

In general, the arabica coffee bush grows at altitudes ranging from 800 to 2,000 metres and it is cultivated in plantations. The arabica coffee obtained from these plants has levels of caffeine ranging from 1% to 1.5% or even lower, which is a significant difference to robusta coffee, which has levels of 3%.

ROBUSTA COFFEE:

Robusta coffee is just one of the species of the varieties of the Canephora species, but due to its global importance, its name was taken for the species, thus identifying canephora with robusta. The most important varieties are Comilón, Kouilloi, Niaouli and Uganda,amounting to 30% of the global production.

This species was discovered when it was observed that it was immune to the Hemiliea Vastatrix plague of fungus that decimates arabica coffees, which is where it gets its name from. Originally from Zaire, the main crops are in low and dry areas of Africa, Indo-China and Brazil. They are coffees with a higher content of caffeine, from 2 to 4%, with a yellowish bean that smells of dry straw. The roasting process is normal and produces a strong, full-bodied coffee that is dark in colour and leaves a hint of bitterness on the palate.

CAFFEINE

The rate of metabolisation of caffeine in a standard organism is around 100 mg every 2 hours, with all caffeine from an arabica espresso being removed, whereas double the time is needed for a robusta.

Caffeine is an alkaloid that stimulates the nervous system and the blood flow. It increases intestinal motility and has a diuretic effect.

The caffeine content in a cup varies depending on the preparation method or the variety of coffee used.

The caffeine is distributed throughout the body, it does not accumulate in one place, which means that the effects are temporary, beginning 15-20 minutes after ingestion.

Moderate doses of caffeine (1 to 3 cups per day) lift your spirits and improve your intellectual and psychomotor performance.

ROAST AND BLEND

The coffee roast type is determined by the area in which this is carried out in Europe. That way, the coffee is produced according to the tastes of the consumers in each place. CAFÉS BAQUÉ carries out the so-called “Cappuccino Roast” which, together with the method of roasting coffee beans of different origins separately, gives an extremely high-quality result.

By subjecting the coffee beans to the heat during the roasting process, different substances are released that are contained inside the cells that make up the bean: fats, sugars, proteins, lipids, etc. Through the roasting process, these substances are released and produce different aromas and flavours.

The roasting process consists of 3 phases:

- Drying: Loss of humidity, from 13% to 1%.

- Expansion: Gases are formed, increasing the pressure in the cells (20-25 atm). The skin comes away. It increases in size.

- Chemical reactions: The Maillard reaction occurs. The aroma and flavour are produced. The fats increase.

The longer or darker the roasting process, the more bitter the coffee will be. It will also be darker in colour and will mask possible defects. If the roasting process is shorter or lighter, the flavour of the coffee will be more acidic (a quality to be enhanced in premium range coffees), maintaining its freshness and good organoleptic qualities, such as fruity aromas and flavours of vanilla and chocolate.

BLEND

The blending process is one of the most important stages for achieving a final flavour that contains the level of acidity, taste, aroma and body that its market demands.

When tasting single-origin coffees, you will notice that they have more or less of the qualities mentioned above, but that it is difficult for them to fulfil all characteristics completely or satisfactorily. That is why coffees of different origins are blended to create the desired flavour for a specific coffee reference, balance.

If you want to add acidity to the blend, you can use washed arabicas grown at altitude, such as those from Colombia, Kenya, Guatemala, etc., which will also give the coffee a pleasant aroma and subtle flavour. Natural arabica coffees, such as those from Brazil, give the blend taste, aroma, a fuller body and more neutral acidity, which contributes a lot to the final result. To give a blend body, you can use a robusta coffee, preferably the most neutral and clean robusta, i.e. without strange flavours or harshness. However, a high percentage of robusta in a blend would destroy the virtues of the other coffee beans that make up the blend.

The possibilities are endless, as are the results. The presence of expert tasters and access to many different types of coffee are fundamental for achieving the right blends for the different tastes of the consumers and for the different ways of preparing a cup of coffee.

COFFEE PRESERVATION AND PACKAGING

Coffee, in its various stages from collection to green coffee, can last a few weeks without losing any quality by simply avoiding excessive humidity or heat.

The green coffee bean keeps all of its potential aromas intact for a long period of time (up to 2 years). However, once roasted, degradation processes begin to occur in a brief period of time (35 days after the day of roasting, the oils around the bean will have oxidised, leading to the coffee becoming rancid).

There are three key factors:

- The loss of aroma: the aromatic molecules formed in the coffee bean during the roasting process tend to move to the surface and are released from there. The time that passes between the roasting of the bean and its consumption should be the shortest possible, as the more time that passes the greater the loss of aroma. On the other hand, coffee is an unstable substance, it absorbs all aromas and smells within its vicinity if it is not stored in the right container.

- Humidity: recently-roasted coffee has a humidity level of 1 to 3%, which makes it highly hygroscopic, i.e. it tends to capture humidity from the atmosphere and this process affects its quality.

- Oxidation: oils and fats make up 15% of roasted coffee. Oxygen from the air causes chemical oxidation, making them turn rancid, as well as the degradation of many other compounds. This process is facilitated by humidity, high temperature and light.

This degenerative process is enhanced by grinding the coffee, as by doing so, you increase the surface of the coffee that is in contact with the air. If, for the coffee bean, the optimum consumption period is 35 days after roasting (once the packaging has been opened), for ground coffee, it is 6-8 hours, after which it will lose more than 70% of its aromatic properties and flavour. A good system of preserving the coffee will delay the loss of aromas and will protect the coffee from humidity, air, heat and light. That is why it is so important for the packaging materials and technology used to ensure optimum levels of preservation: vacuum packaging, aroma valves, opaque and insulating materials, inert gas injection (nitrogen or CO2), etc.

DIFFERENT WAYS OF PREPARING COFFEE

The different ways of understanding coffee that exist in the world can be seen by looking at the different ways of preparing it.

MOKA POT

Invented in 1930 by the Italian Alfredo Bialetti, today it is one of the most common methods used in Spanish homes, approximately 60% of the population uses it. It is thought that this success is due mainly to the fact that the resulting coffee is the most similar to that obtained by an espresso machine, the reference coffee in countries such as Spain, Italy and Portugal.

Tips:

- Use mineral water.

- Always fill the water up to the lower edge of the safety valve.

- Do not press the coffee down too much, otherwise the water will not be able to pass through it.

- Before serving the coffee, stir with a spoon to blend the product.

- Clean the coffee pot without using soap and dry it properly to prevent mould from forming.

- The fineness of the grind should be slightly larger than that used for an espresso machine.

FILTER, DRIP OR ELECTRIC COFFEE MACHINE

Invented in 1907 by the brand Melitta Benz. Although in Spain less than 25% of homes use it, globally it is the most popular system, particularly in the US and northern Europe.

Tips:

- Use mineral water.

- Dampen the paper filter before placing it in the machine in order to prevent any taste of cellulose.

- Do not fill the paper filter too high in order to prevent the water from overflowing.

- Before serving the coffee, stir with a spoon to blend the product.

- Clean the coffee machine without using soap.

- The fineness of the grind should be a lot larger than that used for an espresso machine, as the only pressure that exists in this case is atmospheric pressure.

CAFETIÈRE

It is a system that is hardly used in Spain, but it is one of the easiest methods of preparation. Ideal for the consumption of premium range single-variety coffees.

Consejos:

- Use mineral water.

- Adapt the amount of coffee depending on the preferences (approx. one soup spoon per cup).

- Pour the water in a few seconds after it has boiled.

- Let the mix rest for 3 minutes before lowering the plunger.

- The fineness of the grind should be slightly larger than that used for an espresso machine or Moka pot.

VACUUM COFFEE MAKER

This vacuum coffee maker has an attractive look and is designed for preparing coffee at the table. It is made up of two glass chambers with a central tube and is complemented by an alcohol stove and a tripod. The coffee must be finely ground and the right amount must be added for the number of cups that you wish to prepare. This coffee is added to the upper chamber and the corresponding cold water is added to the lower one.

Both chambers are screwed in to close the coffee maker and thus create the vacuum. This coffee maker is placed on the lit alcohol stove, whereby the water will heat up and, upon reaching boiling point, move up to the upper chamber. The coffee should be left to infuse for three or four minutes. Once the coffee maker is removed from the stove, a vacuum is formed in the inner container and the coffee infusion will go back down to the bottom, absorbed by the force of the vacuum. The sum of the pressure, infusion and temperature combined in this coffee maker produces a bitter but subtle coffee, full of flavour and rich in aroma.

ESPRESSO COFFEE

It is the most popular system in Mediterranean countries, particularly Spain, Portugal and Italy.

This is where Luiggi Becerra and Desiderio Pavón invented the first coffee machine in 1901, which has evolved over many years into the top range electronic machines produced today, which allow us to achieve ideal extractions for natural coffee.

The espresso coffee machine (the name refers to the quick preparation) provides continuous production of cups of coffee, as well as hot water for infusions and steam for heating milk.

The scientific definition of espresso is:

A multi-stage drink prepared with roasted ground coffee and water. It is made up of a thin layer of foam measuring 3-4 mm, which is formed by small bubbles of gas on an emulsion of oils in an aqueous solution made up of sugars, protein, caffeine and suspended solids (coffee grounds).

The main elements of an espresso coffee machine are:

- Boiler..

- Heat exchanger.

- Dispensing unit.

- Filter holder.

- Pre-infusion system.

- Motor pump.

- Water dispenser.

- Water and steam taps.

Parameters for the perfect espresso:

- Amount of water, 30 ml (+/-5).

- Temperature of water in the cup, from 68 to 74 degrees.

- Colour of the foam, reddish hazelnut, perhaps with brown stripes referred to as “tigratura”.

- Thickness of the foam, 3-4 mm. It should linger.

WATER

Around 98% of a cup of coffee is water, so it is vital to take care of this element. Keeping certain parameters in optimum conditions will allow you to produce cups of coffee with the maximum aroma and body. It has such an impact that just by changing the type of water, you can go from producing an excellent cup of coffee to one that is completely insipid, also affecting the colour and texture of the foam.

Below is a list of the water parameters to be taken into account and the value ranges they must fall into in order to achieve the best from each coffee.

1. Conductivity measurement in microsiemens (µS)

- From 200 to 800 µS is acceptable.

- Its presence indicates the level of mineral salts, i.e. elements with an electrolytic charge (ions: with a positive charge cations, or with a negative charge anions).

- Standard readings are between 600 to 1,500 µS

- Problematic waters have more than 1,500 µS.

2. Total hardness measurement, in German degrees dGH, or French degrees fTH

This value indicates the volume of salts (carbonates, sulphates, nitrates, etc.) dissolved in the water, its ratio between scales is as follows:

- 1º dGH = 1,79 fTH = 17,8 ppm

- 1º fTH = 0,56 dGH = 10,0 ppm

- 1 ppm = 1 mg/L

- 50 ppm = 50 mg/L = 100 µS/cm

A “normal” hardness would be from 8º dGH to 15º dGH

The absence of total hardness is a symptom of the acidity of the water.

3. Carbonate hardness measurement, ºKH. It is a component of the total hardness of the water and indicates the hardness composed by carbonates (of calcium or magnesium). This hardness, also referred to as temporary, is responsible for the calcium precipitation when the temperature of the water rises.

Its ideal presence in water is around 4ºKH, a lower level has a negative impact on the quality of the cup of coffee, and an excessively high level causes calcification in the machines.

4. pH measurement: it indicates the level of acidity of the water, with its ideal level being around 6.5. The lower the pH level, the higher the level of acidity, whereas the higher the pH level, the higher the level of alkalinity.

5. Lastly, other elements to take into account: In terms of anions: chlorides (the higher the number, the more problems there will be with corrosion in the machines), nitrates, sulphates, phosphates, nitrites and others.

In terms of cations: sodium (in excess, it also causes corrosion), potassium, calcium, magnesium and others.

ORIGINS OF COFFEE DRINKING

Brazil

Brazil is the world’s primary producer of coffee, reaching between 55 and 60 million sacks (60 kg per sack) per season, thus representing more than a third of the global production. Coffee alone represents 3% of Brazil’s exports, with 8 million people living directly or indirectly from coffee. The total area under cultivation in Brazil is 2.1 million hectares divided into around 300,000 farms, of which two thirds belong to small producers.

The coffees of Brazil, many of which are processed using the dry method, are quite diverse. Those that are exported from the Port of Santos, above all strictly soft coffees, are considered to be the mildest. Coffees from Sul de Minas are very well-known in the global coffee market, with more body and a stronger fragrance. Coffees from Rio are very particular, with an iodine-like flavour that is referred to as the “Rio flavour” or “riado”.

Brazil is a patchwork of flavours: Paraná, São Paulo, Bahía, Espíritu Santo (historically the coffee of the popes)…That is why it is very difficult to classify coffees from Brazil under one label. Among Brazil’s coffees, it is important to highlight the production of a robusta coffee called Conilon, grown mainly in the Rondonia regions.

In Brazil, the first choice in terms of how to consume coffee is filtered coffee, with most coffee consumption taking place at home.

Guatemala

The microclimates that exist in coffee-growing regions determine differences in fragrance, aroma, acidity, body, flavour and aftertaste. In lower areas, from 760 to 1,070 metres above sea level, the plants grow more quickly, which means that they do not have much acidity or body, they are considered to be subtle and pleasant, known as Prime and Extra Prime. In intermediate areas, from 1,070 to 1,200 metres above sea level, these qualities increase. They are referred to as Semi-hard or Hard. In the highest areas, as of 1,300 metres above sea level, the coffee referred to as Strictly Hard is cultivated (SHB = Strictly Hard Bean), highly valued around the world for its peculiar acidity, consistent body, distinct flavour and strong aroma.

They produce 3.5 million sacks of coffee that is hand-picked and is usually processed using the wet method.

Indonesia

Large producer of robusta coffee (85%), with a very bitter taste. Dangerous due to the possible presence of fermented beans. From its arabica production, certain high-quality coffees stand out.

Its total production is around 11.5 million sacks per year.

Colombia

It is the world’s largest producer of washed arabica. Almost 600,000 families live from the cultivation, industry and sale of coffee in Colombia. To speak of Colombian coffee is to speak of the National Federation of Coffee Growers of Colombia, a trade organisation that fights continuously to improve the living and working conditions of coffee growers. Its production of mild, washed coffees comes to 14.3 million sacks.

It is a subtle, acidic coffee, light-bodied but with a pleasant aroma. Among Colombian coffees, the most acidic ones are exported to countries in northern and central Europe, where they value acidity more. The least acidic coffees are exported to Latin American countries.

Ethiopia

The birthplace of coffee, or at least where archaeologists discovered the remains of the oldest coffee growers.

A producer of arabica coffees, both washed and natural. Coffees with very little caffeine. Some are very acidic, produced at an altitude of more than 2,000 metres. Others, such as Djimah, have a wild taste. There are also those that are known for their sweetness, fragrance and subtleness, such as the Harrar coffees. Not to mention Sidamo, Limu, Guji or Kaffa coffee, we could go on…

It produces around 6.6 million sacks per year.

Uganda

With 3.8 million sacks per year, Uganda is now recognised internationally as a producer of robusta coffee, although they also grow arabica coffees of a very high quality. Thanks to coffee promotion programmes driven by organisations such as the Uganda Coffee Federation and the Uganda Coffee Development Authority, they are managing to put the country on the map as a producer of arabica coffee.

Vietnam

In just a few decades, Vietnam has become the world’s largest producer of robusta coffee, whereby the sale of this product represents the third most important contribution to foreign exchange earnings for the country, with a production of currently between 25 and 27 million sacks.

Costa Rica

The coffee of Costa Rica is of the arabica species, with the most common being the Caturra and Catuai varieties. The first comes from the state of Minas Gerais (Brazil) and its name is from the Guarani language, in which Caturra means “small bean”. The cultivation of this coffee was introduced in 1952 and currently represents 65% of the production, with the rest being of the Catuai variety, a mix of Caturra with Mundo Novo (a subtype of Bourbon).

Modern cultivation techniques applied to one of the richest lands on the whole continent due to its volcanic origins, give Costa Rica one of the highest yields per hectare in the world. Plantations in Costa Rica are situated at between 200 and 1,700 metres. Those that are below 700 metres produce a lower-quality coffee with low acidity.

Coffees that grow at more than 900 metres are the ones that provide a higher level of quality, particularly the Strictly Hard Bean (SHB), which grow at more than 1,200 metres. The SHBs of Tarrazú, Heredia or Poas Volcano, are quite complete coffees, medium-bodied, with high acidity and a wonderful aroma.

Kenya

Another of the key producers in terms of quality. Most of its coffees are grown at more than 1,500 metres, and some at more than 2,000 metres. In 1934, Kenya created a supervisory body for coffee called the Coffee Board of Kenya. Its coffees have high acidity, are of high quality and have a high price.

Tanzania

In terms of character, Tanzanian coffee belongs to the family of central and east African coffees, mostly washed, shiny, with a certain level of acidity and balanced in the cup. In recent years, it has become one of the preferred sources of coffee for North Americans, leading to the appearance of coffee beans from this country in important awards for coffee growers.

Despite its huge potential, bad handling and, above all, poor storage and transportation often end up ruining Tanzanian coffee.